Although I’m passionate about politics ever since I was a little boy with all its turns, i’m not planning to talk today about all the ups and downs of what has been going on in the US politics over the last few weeks and in the UK with a change of administration and the implosion of the Conservative party in the UK. There are good commentators on that already on Substack such as Heather Cox Richardson’s Letters from an American and in the UK Matt Goodwin (though a lot of his good stuff you have to subscribe to.

Today is a day of reflection and I’m sitting here listening to one of my favourite pieces of music Mahler’s 2nd Resurrection symphony. I’ve found on Apple Music a great collection of all Mahlers symphonies done by the Berlin Philarmonic which I’ve favourited. This 2nd is one of the best I’ve heard conducted by Andris Nelson.

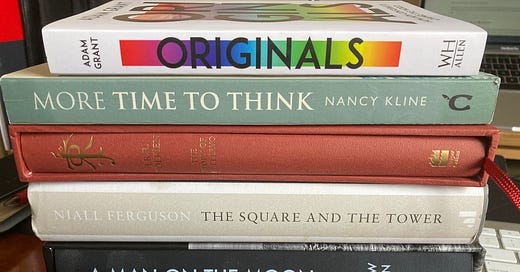

One of the reasons why I enjoy Apple Classical music is the serendipity and I have been introduced to more classical music than I ever would have had if I had had to buy the vinyl or CD. My wife complains about my book collection and I suspect that if I had bought CD’s in the same number we would have had to buy a much bigger house.

I was in two of my external community meetings yesterday, and in one we were discussing factors of change buffeting the KM industry. I was recently on a panel discussion at the CILIP conference in Birmingham with 2 other KM experts. Hank Malik who works for the IAEA and Louise Goswami who is the new Chief Knowledge Officer for the NHS. We were asked about the KM profession and its future.

My thought was that it was the most exciting time to be a KM professional as it was a time of flux and opportunity and a chance to experiment. I reminded them that managers will be seduced by the thought of new tools like AI, but in the end it still comes down to people wanting to share and more importantly apply that knowledge.

I also reminded them that knowledge work is not like working on a production line and that even with the best KM system it will never give you the definitive answer, at best it will give you a 75% answer because knowledge work is not linear it is full of complexity from project to project.

This brings me to the role of curiosity and trust and there have been two excellent posts on this by 2 of my community colleagues - one a expert in PKM (Personal Knowledge Management) who has written on trust and one in learning and development around curiosity.

Bill Ryan is the Learning expert and writes here and his post on curiosity mirrors many of my thoughts

He starts

In the modern business landscape, curiosity isn't just a trait—it's an investment that pays dividends in innovation, adaptability, and growth. It is learning in action driving business results.

An individuals curiosity to me is one of the secret sauces of a companies success and it is encouraged by allowing employees time to reflect on their day to day work and asking one simple question

What did I do today that I can improve on and how do I incorporate it into what I’m doing

The interesting observation that I’ve made over many years is that by and large people want to develop knowledge and share it, its just that organisations find new and intriguing ways to stop them.

I’ve been around enough to remember that when PC’s arrived in the workspace it would relieve workers from some of the drudgery jobs- how did that turn out…

Will it be the same with AI? Will busy workers use AI blindly to ask questions and because they are so busy they use the answers without thinking.

Bill goes on with the following key points that I’ve been using and encouraging people to use both professionally and personally for many years

1. Make learning a part of every project. Ask, "What do we need to learn to make this successful?"

2. Encourage #curiosity. Reward questions as much as answers.

3. Create space for experimentation. Not every new idea will work, but every attempt is a learning opportunity.

4. Share insights freely. Knowledge grows when it's shared.

A complaint over many years is that managers buy and large are still wedded to the Taylorist view of work- ie a worker who isn’t at their desk, head down and working is just slacking. Therefore there isn’t the time for reflection and curiosity unless its in your own personal time.

There are enough people around who are advocating a new way of managing. Two of the most interesting I’ve met are Celine Schillinger through her book ‘ Dare to Unlead” and Charles Handy who has written many books There is a good summary of Celine’s book here in Forbes (one for your summer read)

In the age of AI I would argue that giving time for knowledge workers to be curious to reflect and experiment is the element between success or failure of your organisation going forward.

However we need to make sure that organisations make it easy to access what I call ‘little bet’ money to allow people to develop thoughts and to avoid the concept of the idea becoming inert

That is to say, ideas that are merely received into the mind without being utilised, or tested, or thrown into fresh combinations. (I will talk about the role of communities of practice as the catalyst for this at a later post)

The problem for managers is in trust. Trust your employees that they are professional enough to want to experiment and be curious, but also educate your clients that if they want the best job, then their fees are bring invested so that you don’t get a cookie cutter job but the most creative one

Harold had an excellent post on this area of trust that is well worth a read. I was reminded of a comment many years ago from America that people lost trust in government because government lost trust in the people. (There is some good research on this from Pew Research)

We have seen this also in the UK where the outgoing Conservative government lost trust in its supporters and so its supporters by and large ‘walked to the other side of the road’ Trust once it is lost, takes a long time to rebuild.

I’ve seen senior managers in businesses feel that they can’t trust their staff say about a downturn in business or a scandal. The not telling diminishes ther credibility with staff and means that future messages on anything are treated with suspicion

Harold uses a great quote from Joan Westerberg

Experts and leaders have to shift their values toward transparency, honesty, and humility in their communications and actions, being upfront about the limitations and uncertainties of their knowledge, acknowledging mistakes and failures when they occur, and being open to feedback and critiques. By showing that they are not infallible or above accountability, experts can help to dispel the perception of elitism and disconnection from the public.”

This is important in businesses also as if people don’t think that their knowledge is being used wisely or they won’t be credited through attribution will withhold their knowledge and only use it for their own purposes and will not share it. To paraphrase Bacon - Knowledge only be of good use unless like dung it is widely spread.

And now Mahler has finished and so have I for today.

I do revisit my posts and if there is something more to add I will add an additional post linking back to the original post.

Have a great weekend

Thank you for kind words Andrew. If interested in learning more around curiosity, I highly recommend The Workplace Curiosity Manifesto by Stefaan Van Hooydonk.